Jazz Vocal Phrasing And The Importance of Rhythmic Variation

The pillars of jazz vocal phrasing are rather elusive. What is “good time” and “good feel” in singing? After all, vocalists need not only manage the natural rhythm of a lyric, but they must also juggle between the melody and their place within the rhythm section. There are multiple rhythmic layers at play, yet the greatest jazz vocalists make it sound as effortless as a conversation. I hope these core rhythmic elements and their execution will be explicit through a comparison of a 1929 performance of “Mean to Me” by Ruth Etting and a 1937 recording of the same song by the Teddy Wilson orchestra featuring Billie Holiday.

Scansion

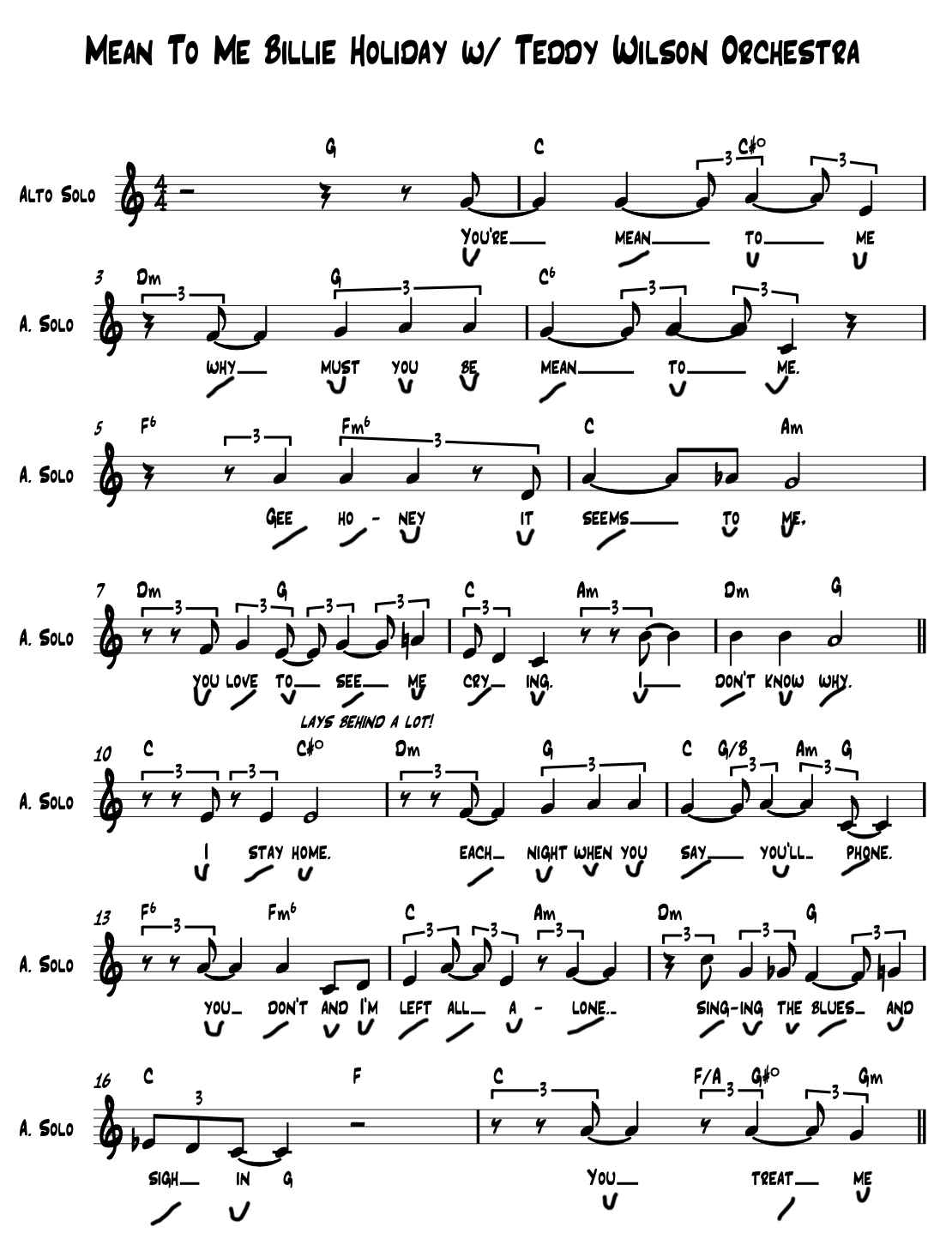

Vocal phrasing differs from instrumental in that there are lyrics, so a musical analysis of “Mean To Me” might warrant a system of scansion. This is a system commonly used in poetry to determine the natural rhythm of a line by analyzing stressed and unstressed syllables typically to place into a meter. In my opinion, it is appropriate to use a similar analysis as singing is an oral tradition just like poetry. Now, one could technically stress whichever word one would like while reading out loud. However, to figure out stress and meaning in scansion, one would focus on inflection and elongation of vowels. I attempted to do so in the most neutral way, and in this song with its ample use of pronouns it is worth noting that pronouns are rarely stressed unless for emphatic effect. Also, while one reads out loud it is almost impossible to stress a pronoun without increasingly stressing the verb following. A great example would be line 4. While one might want to stress “you” it is almost impossible to stress it more than the following verb, so therefore I concluded “you” is unstressed in the context of the following verb “love.” Throughout the song, there seems to be a pattern of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed throughout. There are, however, a few sections where there are two or three consecutively stressed syllables or unstressed syllables, such as lines 2,7 and 15. I placed this “neutral” scansion over the transcription of Etting and Holiday to compare in what ways they were bringing forth the lyric. This way I could compare who is placing the natural stresses of the lyric in a musically stressed position. (I consider a musically stressed position a downbeat, and I particularly consider beat 1 to be the most musically stressed position.) (Scansion is placed in context of the two separate transcriptions at the end of the article).

Holiday’s mastery of the inherent rhythm of the lyrics is incredibly present in her performance. Recall how I brought up the rhythmically diverse spots in the system of scansion. Well, Holiday takes advantage of these spots. She is very economical with her downbeats and rarely places a lyric on them, and this in turn highlights the areas where she chooses to do so.

Moreover, the quarter note triplets from the first and second A in “Figure A” highlight how she devotes the same three unstressed syllables in both sections. Then, her stressed syllable on the lyric “mean” and in the following “say,” sound incredibly emphatic and intentional. There is really no way that she could have stressed these stressed words in a more musical manner.

Etting, because she is phrasing exactly as the songwriters intended, and because she initiates almost every phrase on the downbeat of beat 1, has a lot of unstressed syllables in musically stressed positions.

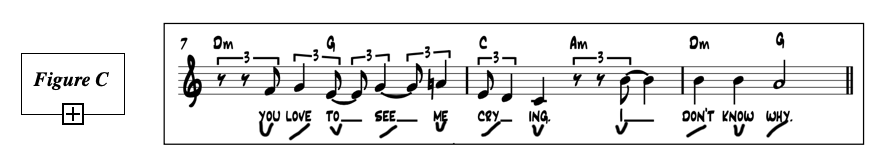

Notice how in “Figure B” she has pronouns on every stressed syllable and the verbs are all on up beats (Figure B). Contrarily, notice how Holiday places all of the pronouns in unstressed positions and the “don’t know why” is all on stressed syllables. Holiday is using her downbeats sparingly, but this in turn makes them emotionally effective.

Similarly, in “Figure D” Ruth Etting again places every word in a stressed position except the one actually naturally stressed word “don’t.” Holiday, on the other hand, places “don’t” and “left in stressed positions as shown in “Figure E.”

Ruth Etting performance

Ruth Etting’s performance of “Mean To Me” was the first recorded version of this Turk and Ahlert song. She is more or less performing the song exactly as the songwriters intended. Although she and the band are a bit out of phase with one another, and this does not appear intentional, I attempted to notate the rhythmic variance in her phrasing. Her sense of the beat is consistently tight (figure F), and so is the band’s, so there are virtually no rhythmic textures at play. (A tight beat signifies when the second eight note in a triplet triplet subdivision falls on the third subdivision and therefore is closer to the following beat’s down beat.) It also appears that it is the band that is controlling this feel.

Her strict adherence to the original form of the song also dictates how she stresses the lyric. Therefore, she always heavily emphasizes beat 1 in every measure, so her phrasing is very straightforward, and there are few rhythmic variances within her performance. This creates a substantial lack of momentum and forward movement, and this in turn leaves the performance stagnant. In fact, the only levels of improvisation and variance at play are her vibrato, vocal dips and glides that she performs on some of the half notes, and this sort of operatic and dramatic glide and vibrato is stylistic for the 1920s vocals where classical voice was considered more or less the only “correct” type of singing.

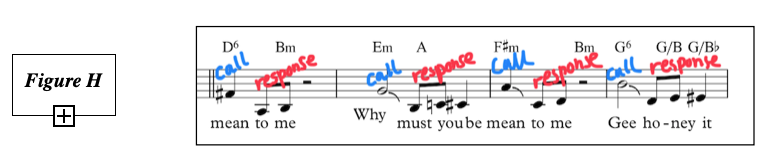

It is also worth noting that she and the rhythm section perform a straight feel on the B section which creates a contrast to the A sections (Figure G). Again, other than a call and response with a clarinet that continues a triplet figure, she is still more or less in sync with the band and not utilizing rhythm as a tool in her vocal phrasing.

Billie Holiday’s performance

Billie Holiday takes many liberties with the melody in her performance. She largely ignores the melodic contour of the A sections where one starts with a high note as sort of a call and then the response is the leap down to the 2 or 3 adjacent notes. “Figure H” shows how Etting does this in a manner that matches the original sheet music:

In Figure I, we see how Holiday largely abstains from this melodic contour. This also further supports my idea that she is more focused on bringing out the natural rhythm of the lyrics as this call and response contour gets in the way of the natural rhythm.

The Teddy Wilson Orchestra emphasizes beat 2 and 4 in their groove, so gauging that Billie Holiday is consistently behind the beat is fairly easy. Therefore, it must also be taken into account that my transcription is only trying to clarify which rhythms she is implying rather than what is occurring metronomically. Contrasting to Etting’s tight beat, Holiday’s beat greatly varies. She constantly switches up which triplet subdivision she accents, and this creates a very fluid, conversational feel, and when she actually sings on the downbeats it feels incredibly compelling. The push and pull between her being in phase and out of phase with the band creates tons of forward motion.

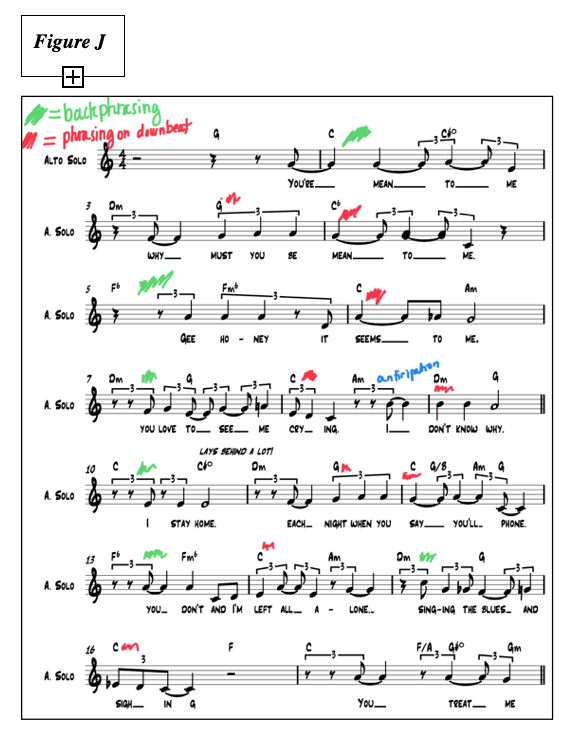

Beyond singing behind the beat, Holiday also utilizes back phrasing in interesting ways that stretch and condense the melodic phrases. “Figure J” displays how Holiday starts most phrases a quarter note or more later than the the written, intended melody; however, she almost always has the backend of the phrase aligned with a downbeat. This is genius and creates even more rhythmic push and pull throughout the form. Not only is she interacting with the melody, the rhythm of the lyric and the band but also the overall form. There are so many dimensions to her sense of rhythm and the way she articulates it.

Outside of rhythmic gestures, Holiday interacts with the lyric, melody and harmony in ironic and inventive ways. She uses the major 7th in the key to create melodic tension as seen in measure 9, 24 and 27. For measure 24 on the D major chord (the one time the V/V chord occurs in the form) the “B” is tension 13. This creates a lot of tension during the end of the B section, and she resolves this melodic and rhythmic tension on the last A where she sings 3 downbeats in a row on the 3rd of the key on the lyrics “it must be” in measure 26.

Holiday also uses the blues to embellish the melody. The most notable place is measure 15 which is a bit tongue in cheek as she is singing about the blues literally. Further, measure 29 is also notable for being the only place where she sings the call and response contour from the “written” melody. Nevertheless, she is not singing the original melody notes here as she sings the b7 of the IV chord (F chord) on the lyric “for”; she is still incorporating the blues and loosely paraphrasing the original melody.

Conclusion

Ruth Etting’s performance was informed by a different school of thought, and she did not have the same advantages of recording technology as Billie Holiday had just 8 years later. Regardless, the evolution of singing and the incorporation of rhythm and speech is evident when comparing the two performances. The jazz vocal idiom relies more heavily on a sense of rhythmic and lyrical conveyance than it does on vibrato, note sustain and tone. Further, I believe a singer can gain “good time feel” through a deep awareness of a lyric’s rhythm as well as understanding how to distinguish and utilize triplet heavy phrases and downbeat heavy phrases, and having a sense of the beat in relation to natural speech is imperative before digging deeply into back phrasing. As you now may wish to analyze some singers on your own, take into account that most singers take more liberties on live recordings, and some singers incorporate “agile phrasing” into their sound. Vocalists like Sarah Vaughan and Billie Holiday tend to vary both the melody notes as well as the time feel more than an artist such as Ella Fitzgerald who tends to sing the song a bit more “pure”- meaning how the melody is written in the sheet music. Further, you will frequently hear instrumentalists take great creative liberties with the melodies. Take for instance Coleman Hawkins’ iconic take on “body and soul” - the melody is almost unrecognizable. The next article will look at some more extreme phrasing from Sarah Vaughan and Anita O’Day, but for now, let me know your thoughts? Is scansion a good system for analyzing jazz vocalists?